When we talk about the Gujarat Riots of 2002, we’re diving into one of the darkest and most debated chapters in modern Indian history. It’s a story layered with pain, politics, anger, and endless arguments that, even today, can spark fiery discussions. Whether you were old enough to remember it happening live on TV, or you’ve only read about it in history books, there’s no denying the sheer weight the year 2002 carries for Gujarat — and for India as a whole.

Let’s rewind a bit and try to walk through what really happened, how it escalated, and why it remains such a touchy subject even after more than two decades.

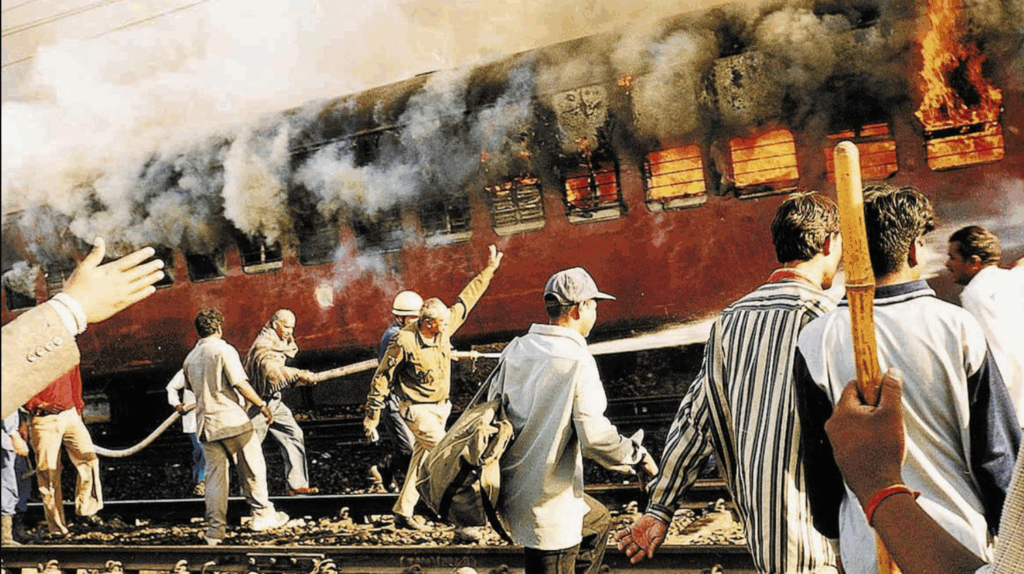

The Spark: Godhra Train Burning

Everything began on the morning of February 27, 2002. A train called the Sabarmati Express was moving through the town of Godhra in Gujarat. Onboard were a large number of Hindu pilgrims, mostly karsevaks returning from Ayodhya after a religious ceremony linked to the Ram Janmabhoomi movement.

Around 7:45 AM, as the train stopped at Godhra station, an argument broke out between some passengers and local vendors. Things escalated quickly. Allegedly, a mob attacked the S-6 coach of the train, and in the chaos, the coach was set on fire. 59 people — including women and children — were burned alive.

The images that came out were horrifying. Charred bodies, burnt belongings, and a sense of disbelief spread like wildfire across the state.

For many, this wasn’t just seen as a random act of violence — it was interpreted as a targeted attack on Hindus.

The Fire Spreads: Riots Across Gujarat

What followed after Godhra was an eruption of violence that Gujarat — and India — hadn’t seen in decades.

Starting from February 28, Gujarat witnessed brutal communal riots. Within hours, mobs took to the streets, and the violence became unimaginable. Muslim homes, shops, and mosques were targeted. Entire neighborhoods were burnt down. People were dragged out of their homes. There were chilling reports of rape, looting, and murder.

Areas like Ahmedabad, Vadodara, Anand, and Mehsana turned into literal war zones.

In some places, police either couldn’t control the mobs or were accused of standing by silently — or even worse, participating. The government, led by then Chief Minister Narendra Modi, faced huge criticism for allegedly not doing enough to stop the violence.

Official numbers said about 1,000 people were killed, the majority of them Muslims. But human rights organizations and activists have long argued that the real death toll could be much higher, maybe even over 2,000.

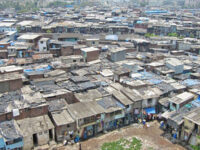

Thousands of people were displaced, living in makeshift camps, stripped of their homes, their dignity, and their sense of safety.

The Role of the State: A Huge Controversy

One of the biggest and most painful debates about the 2002 riots is the role of the Gujarat state government.

Many critics accused the government — and especially Narendra Modi — of either failing to stop the riots or actively enabling them through inaction or worse, complicity.

Reports and testimonies from that time suggest that there were warnings about the potential for violence after the Godhra incident, but very little was done to preemptively control the situation. Curfews were imposed too late in many areas. Forces were deployed slowly.

And then there were the deeply disturbing allegations: that politicians, police officers, and local leaders gave mobs free rein or even directed them.

A famous quote attributed to Modi from that time — though he has denied ever saying it — suggested that “every action has a reaction,” hinting that the violence was somehow an inevitable response to Godhra.

Whether or not there was direct state-sponsored violence, the reality is that the state machinery utterly failed to protect its citizens when they needed it the most.

Zakia Jafri and the Quest for Justice

One name that always comes up when talking about the Gujarat Riots is Zakia Jafri. Her husband, Ehsan Jafri, was a former Member of Parliament. He was brutally killed during the riots at the Gulberg Society massacre, where a mob attacked and slaughtered dozens.

Zakia Jafri became one of the most determined voices seeking justice, filing a petition accusing Narendra Modi and other top officials of being part of a larger conspiracy.

After years of legal battles, the Supreme Court ultimately cleared Modi of wrongdoing, citing lack of evidence. However, the scars left behind by these court cases remain, and they continue to divide public opinion to this day.

Media and Public Perception: Two Different Indias

The Gujarat Riots also marked a new kind of media war in India.

On one hand, TV channels showed the gory details: burnt bodies, weeping mothers, angry mobs. Some journalists risked their lives to report the truth from the ground. Outlets like Tehelka did sting operations years later that revealed confessions from rioters admitting they were aided by politicians.

On the other hand, a large section of society rallied around the narrative that the riots were a spontaneous reaction to the Godhra train burning. Many in Gujarat — and across India — believed that Hindus were under threat and that the government had defended them.

This split in perception — between seeing the riots as an act of genocide versus seeing them as a tragic but understandable backlash — is a divide that still persists.

Long-Term Impact on Politics

Whether you view him as a hero or a villain, there’s no denying that Narendra Modi’s political career was shaped by 2002.

Despite national and international outrage, Modi survived politically. In fact, he won the December 2002 Gujarat Assembly elections with a massive mandate. Many Gujaratis saw him as a strong leader who stood up for Hindu interests.

Over time, Modi carefully crafted his image, moving from a divisive figure to a pro-development icon. By 2014, he rode that wave all the way to becoming the Prime Minister of India.

But the ghost of 2002 has never entirely left him. Every election, every major speech, every foreign visit — questions about Gujarat and 2002 have followed him like a shadow.

Healing and the Lack of Closure

For the victims, closure has been a slow, painful, and incomplete process.

Many of the camps where riot victims took refuge turned into permanent slums. Justice came late — or not at all — for most. Some high-profile convictions did happen, like in the Best Bakery case and the Naroda Patiya massacre, where leaders like Maya Kodnani (a former BJP minister) were initially convicted, though later acquitted.

Still, a lot of victims feel that justice was neither full nor fair.

Meanwhile, Gujarat has moved on economically. Cities have flourished, highways have been built, industries have boomed. But beneath the surface, religious divides remain raw in many places.

Some neighborhoods have become completely segregated — Hindus and Muslims living apart, suspicious of one another.

Healing from something as massive and traumatic as 2002 isn’t just about rebuilding homes. It’s about rebuilding trust. And that’s a journey Gujarat is still very much on.

The Global Response

Internationally, the Gujarat Riots put India under a harsh spotlight.

For years, Modi was denied a visa to the United States over concerns about his alleged role in the violence. Human rights organizations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch published scathing reports.

But politics, as always, evolved. After Modi became Prime Minister, Western nations rolled out the red carpet. Trade and diplomacy took precedence over old accusations.

Still, even today, if you talk about Gujarat in international human rights circles, 2002 remains the most frequently cited event.

Final Thoughts: Why 2002 Still Matters

The Gujarat Riots of 2002 aren’t just an event in the past. They’re a mirror.

They force us to ask tough questions about what kind of society we are building. How easy it is for hatred to explode. How fragile the line between civilization and chaos can be.

It’s a story about loss — of lives, of trust, of innocence.

But it’s also a story about memory. About how important it is to remember even the things we’d rather forget. Because only by remembering can we hope to build a future that doesn’t repeat the mistakes of the past.

For many Indians, Gujarat 2002 is a wound that never fully healed. And maybe it never will. Maybe the best we can do is keep telling the story — honestly, openly, and bravely — so that it never happens again.

0 Comments